Blackstone only "discovered" what had already been discovered

By Mack H. Scott III in UpRiseRI

The answer is quite simple – The continued celebration of Euro-American “firsts” devalues the historical significance of the Indigenous people whose tenure preceded that of the colonists. This is certainly true for the memorialization of William Blackstone because the reverend’s only notable accomplishment was being the first white man to settle in what would become Boston Massachusetts and later Cumberland Rhode Island.

But when Blackstone made his way to what the Native people called Wawepoonseag – the place for catching birds – in 1635, he followed the well-worn paths created and traversed by Indigenous peoples.

Wawepoonseag – now known as Cumberland—was a managed

landscape and far from the unbridled wilderness biographers have supposed.

Indigenous peoples had removed the trees along either side of the Pawtucket

River creating a grassland preserve teeming with wild fowl. They also carefully

managed the flow of the Pawtucket producing a tributary brimming with salmon.

The bounty that William Blackstone found at Wawepoonseag was not happenstance. Instead, the abundance resulted from the labors of Indigenous men and women who created and maintained the complex ecosystem that made Blackstone’s settlement at Wawepoonseag possible.

If we narrowly focus on the commemoration of

Blackstone as the first white settler in a landscape already populated and

cultivated by Indigenous persons, we render the efforts and experiences of

these people as unimportant, or at least unworthy of memorialization.

It is believed that after obtaining permission from Osamequin – the principal sachem of the Wampanoag – and Miantinomo – a chief sachem of the Narragansett – to settle in Wawepoonseag, Blackstone lived peaceably among his Indigenous neighbors. Although there is some evidence of disputes arising over livestock, Blackstone did likely get along with his new neighbors.

It was reported that Blackstone was fluent in the Algonquin language and that he regularly preached to local Natives. Also, Blackstone arrived in Wawepooneag alone – save for an unknown number of persons only referred to as servants – and thus would have most likely tried to avoid conflict at all costs. What is less clear is why the Natives would allow Blackstone to make his home at Wawepoonseag.

Traditional

historical interpretations suppose that the Indigenous people in this region

were just extraordinarily friendly and generous. And that they simply gave away

their ancestral lands to men like Blackstone and Roger Williams.

Such postulations are reductive, illogical, and not supported by historical evidence. Blackstone likely brokered his tenancy through reciprocity. Blackstone’s biographers recorded that he regularly traded with and entertained Indigenous people at his home in Wawepooneag.

Also, Blackstone often traveled with Williams to Cocumscussoc-a trading post close to the seat of the powerful Narragansett sachemship in what is today south county Rhode Island. It is possible that these cross-cultural exchanges were emblematic of the social and economic obligations Blackstone maintained as part of his residency at Study Hill.

After the attack on a Narragansett stronghold in 1675, the Natives

reclaimed Wawepooneag and MAs was true for the settlement five miles away in

Providence, the Natives reclaimed their land when the settlers no longer met

their obligations.

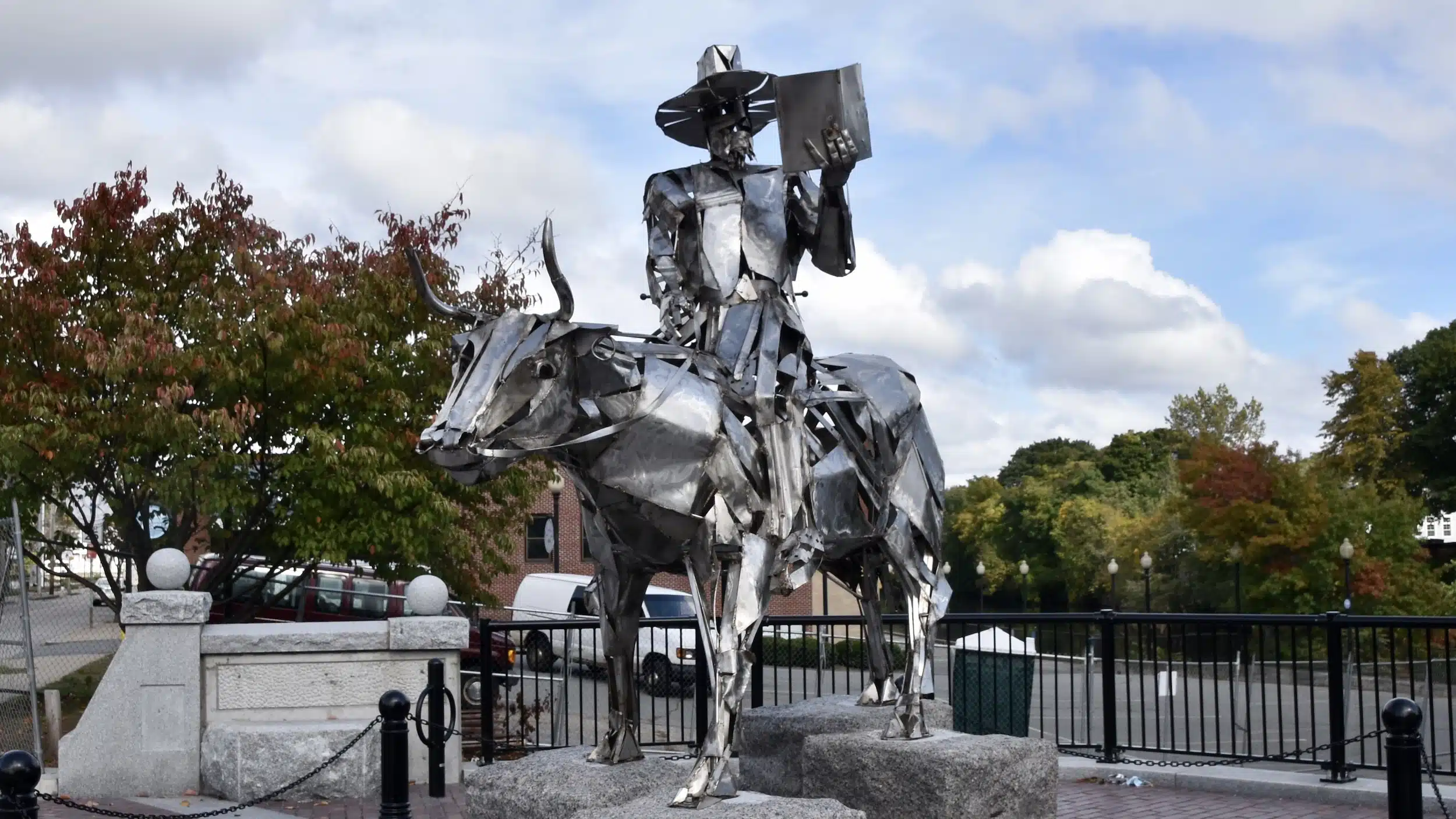

A

monument communicates more about the community who decided to erect it than it

does about the people, events, or ideas being memorialized. And the Blackstone

monument reveals our continued preference for celebrating the deeds and

experiences of Euro-Americans. The monument obscures Wawepoonseag’s Indigenous

roots and makes the history of the region before Blackstone’s arrival seem

inconsequential.

We might be forgiving to earlier generations who erected monuments to immortalize their one-sided and incomplete historical interpretations, but in the twenty-first century, these acts are absurd. The stories we now tell must be inclusive. And if we chose to celebrate the history of a place, we should seek to incorporate the stories of all those diverse pioneers whose labor and sacrifice have made that place honorable.

In a state woefully lacking in the

public acknowledgment and commemoration of its Indigenous roots, a monument to

Blackstone simply for being the first white man to settle in Rhode Island is

disgraceful.