Why there are laws against storing them insecurely

Gary Ross, Texas A&M University

|

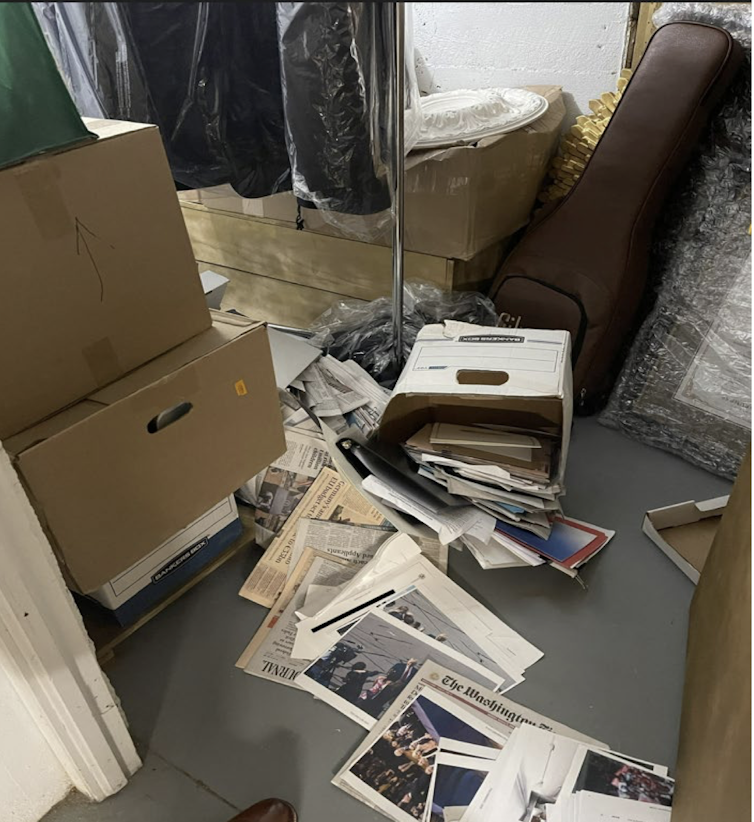

| Boxes containing classified documents are stored in a bathroom of Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club. Department of Justice |

When Donald Trump pled not guilty on June 13, 2023, to federal criminal charges related to his alleged illegal retention of classified documents, it was his first opportunity to formally answer charges that he violated the Espionage Act.

The Justice Department alleges that, after his presidency, Trump held, in an unsecure location, documents about some of the nation’s most sensitive secrets, including information about U.S. nuclear programs as well as U.S. and allies’ defense and weapons capabilities and potential vulnerabilities to military attack and that he repeatedly thwarted efforts by the National Archives to retrieve them.

The Conversation asked Gary Ross, a scholar of Intelligence studies, who has investigated cases involving the mishandling and unauthorized disclosure of classified information for multiple U.S. government agencies, to define some of the categories of risk detailed in the indictment and explain how the U.S. and allies may have been harmed.

What’s the risk to US national security?

U.S. national security includes the country’s ability to defend itself, collect and analyze sensitive information about other nations’ capabilities and intentions, and maintain relationships with allies. National security can be compromised in a variety of ways.

Americans are familiar with espionage, or spying. It’s when a government recruits an official or resident of another country – just as the Soviet Union recruited Robert Hanssen, a senior FBI special agent, in 1979 - to provide classified U.S. intelligence.

But the Espionage Act is much broader than traditional spying and includes the unauthorized possession, storage or disclosure of classified information.

According to the federal indictment, Trump stored boxes containing various levels of classified material in different parts of The Mar-a-Lago Club, his Palm Beach, Florida, resort. Boxes were kept on a ballroom stage, in his bedroom and in a bathroom and shower between Jan. 20, 2020, when he left the White House, and Aug. 8, 2021, when the FBI recovered 102 classified documents.

Trump had returned some classified material on Jan. 17, 2021, and June 3, 2021.

This was particularly concerning because, according to the indictment, Mar-a-Lago was the site of more than 150 social events, attended by tens of thousands of people, between January 2020 and August 2021.

|

| Boxes full of classified documents sit on top of an ornate stage inside the Mar-a-Lago Club’s White and Gold Ballroom. Department of Justice |

If foreign spies knew Trump stored classified documents at Mar-a-Lago, they may have attempted to enter the property. In 2019, a Chinese business consultant entered the resort and initially got past Secret Service agents. She was stopped in the main reception area, carrying multiple electronic devices.

What’s the risk to sources and methods?

The U.S. uses sources and methods such as spy satellites and foreign citizens or assets to clandestinely gather information about other countries.

Based on the classification markings identified in the indictment, documents Trump stored at Mar-a-Lago contained intelligence from multiple U.S. sources, including satellite images, human sources and intercepted foreign communications, which can include cell phone calls or email messages.

If other countries gained access to this intelligence, their counterintelligence professionals could learn how the U.S. obtained specific information and they could use countermeasures that could render a particular source or method useless to the U.S. moving forward.

In April 1983, a terrorist attack killed 63 people at the U.S. Embassy in Beirut. At the time, the terrorist organization operating in Syria was communicating with counterparts in Iran. The U.S. government began intercepting the traffic, which two media outlets later reported, according to an opinion piece by Katherine Graham published in The Washington Post.

Shortly after, communication between Syria and Iran stopped and the U.S. intelligence community lost insight into the Syrian terrorists’ activities. This may have left the U.S. unable to detect or prevent an attack by the same terrorist group on the Marine barracks in Beirut six months later. That attack left 241 U.S. service men and women dead.

What’s the risk to US foreign relations and alliances?

Diplomacy, the connection between sovereign states, largely forged through foreign policy, is an important component of national security, as is intelligence sharing among allied intelligence services.

|

| Classified documents meant to be seen only by the Five Eyes intelligence alliance and newspapers spill onto the floor of a storage room of the Mar-a-Lago Club. The Department of Justice |

But, the allegation that a document with Five Eyes classification markings had spilled onto a Mar-a-Lago storage room floor may lead the other four countries to reconsider their level of information sharing with the U.S. It has happened before.

After the 9/11 terrorist attack, a report by the Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction documented two instances in which allied intelligence agencies refused to share sensitive information with the U.S. due to concerns that the U.S. would not protect the information.

What are the risks to soldiers and citizens?

In addition to information about U.S. nuclear programs, U.S. and allies’ defense and weapons capabilities and potential military vulnerabilities, the indictment alleges Trump also unlawfully retained classified information about U.S. military retaliation plans in response to a foreign attack.

In enemy hands, this intelligence, if still valid, could significantly increase their ability to develop effective countermeasures or to alter their military tactics. At best, this could prolong a conflict, and, at worst, could allow an adversary to defeat U.S. forces, which could jeopardize citizens’ lives.

In each scenario, the lives of U.S. service members could be placed at increased risk.

Additionally, an enemy able to identify a U.S. vulnerability, particularly a self-identified vulnerability, can also try to exploit that weakness to their advantage, just as the United States did during World War II.

Prior to the 1942 Battle of Midway, U.S. intelligence intercepted and decrypted communications detailing Japan’s military strategy for the upcoming battle.

U.S. forces took advantage of the information, won the decisive conflict and turned the tide of the war.

Ironically, the U.S. was unsuccessful in safeguarding the fact that it had intercepted and decrypted Japanese communications. A Naval officer allowed a Chicago Tribune journalist unauthorized access to classified U.S. communications.

The journalist subsequently wrote an article revealing the U.S. penetration. This was one of the few instances in which the U.S. government considered, but ultimately rejected, prosecuting a media outlet for disclosing national defense information.![]()

Gary Ross, Associate Professor of Intelligence Studies, Texas A&M University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.