How an Old Law Is Helping Fight New Plastic Problems

On October 15 a

federal court approved the largest citizen-suit settlement ever awarded under

the Clean Water Act: $50 million.

On October 15 a

federal court approved the largest citizen-suit settlement ever awarded under

the Clean Water Act: $50 million.

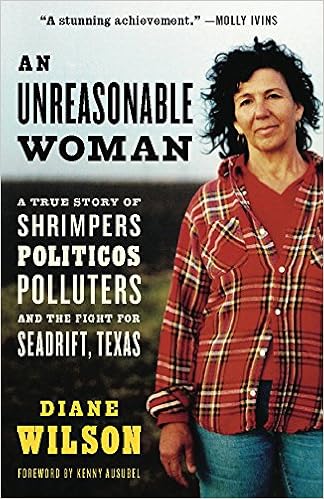

A fourth-generation

Texas shrimper, Diane Wilson, used the citizen suit provision of the Clean

Water Act to sue the petrochemical manufacturer Formosa Plastic for violating

the Clean Water Act. Formosa was discharging plastic pellets into Lavaca Bay, a

water body located off the Gulf of Mexico halfway between Houston and Corpus

Christi.

In the recent fight

against plastic pollution, advocates and lawmakers have focused their attention

on enacting new laws like plastic bans.

But Wilson’s victory is a reminder that enforcement of existing laws is still a valuable tool in battling plastic pollution — and citizen suits can be leveraged to hold industry accountable.

But Wilson’s victory is a reminder that enforcement of existing laws is still a valuable tool in battling plastic pollution — and citizen suits can be leveraged to hold industry accountable.

To understand how this

works, let’s go back almost 50 years.

The Clean Water Act

was a part of the “burst” of federal environmental legislation enacted in the 1970s in response to

perceived inadequacies in common law.

Like its contemporary environmental statutes of the 1970s, the Clean Water Act contains a citizen suit provision allowing private citizens to sue facilities suspected of violating the law.

But unlike its contemporaries, a violation of this particular law is relatively easy to prove. If a facility discharges a pollutant into water without a permit, a violation has occurred.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Diana was a leading environmental activist back in the 1980s when I served as national organization director for the group now known as the Center for Health and Environmental Justice. She was an inspiration then and still is. -Will Collette

The Clean Water Act also allows plaintiffs to sue for monetary penalties of up to $25,000 per day for violations (paid to the U.S. Treasury), a remedy that’s not available through other environmental statutes. As a result more citizen-suit provisions have been brought under the Clean Water Act than under any other environmental statute.

Like its contemporary environmental statutes of the 1970s, the Clean Water Act contains a citizen suit provision allowing private citizens to sue facilities suspected of violating the law.

But unlike its contemporaries, a violation of this particular law is relatively easy to prove. If a facility discharges a pollutant into water without a permit, a violation has occurred.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Diana was a leading environmental activist back in the 1980s when I served as national organization director for the group now known as the Center for Health and Environmental Justice. She was an inspiration then and still is. -Will Collette

The Clean Water Act also allows plaintiffs to sue for monetary penalties of up to $25,000 per day for violations (paid to the U.S. Treasury), a remedy that’s not available through other environmental statutes. As a result more citizen-suit provisions have been brought under the Clean Water Act than under any other environmental statute.

Formosa manufacturers

lentil-sized plastic pellets called nurdles — the raw material for everyday

plastic products. Because of their size, the pellets are difficult to remove

from the environment and are easily ingested by marine life.

The company’s Clean Water Act permit prohibited the “discharge of floating solids or visible foam in other than trace amounts,” but for several years Wilson noticed that pellets were being discharged almost daily from outfalls at the Formosa plant in Point Comfort, Texas, into Lavaca Bay. She also noticed a measurable decline in shrimp, crabs and mullets.

The company’s Clean Water Act permit prohibited the “discharge of floating solids or visible foam in other than trace amounts,” but for several years Wilson noticed that pellets were being discharged almost daily from outfalls at the Formosa plant in Point Comfort, Texas, into Lavaca Bay. She also noticed a measurable decline in shrimp, crabs and mullets.

You

saw that #Nurdles

float, but they also get trapped in sediment. You can see them throughout this

exposed soil profile here that was covered with a layer of clay and rock before

erosion exposed them again.

With her livelihood at

stake, Wilson took action.

Using the citizen suit

provision of the Clean Water Act, she, along with the San Antonio Bay Estuarine

Waterkeeper, filed suit against Formosa in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas

in 2017, alleging that the petrochemical manufacturer was violating its permit

and thereby the Clean Water Act.

At a bench trial in March 2019, a federal judge reviewed more than 2,400 samples of plastic, as well as 110 videos and 44 photos from Lavaca Bay. After considering the evidence and hearing from multiple witnesses including several experts, the court ruled in Wilson’s favor.

At a bench trial in March 2019, a federal judge reviewed more than 2,400 samples of plastic, as well as 110 videos and 44 photos from Lavaca Bay. After considering the evidence and hearing from multiple witnesses including several experts, the court ruled in Wilson’s favor.

In its June 2019

order, the court found that Formosa’s discharges consistently exceeded “plastics

of more than trace amounts.” Ultimately the evidence demonstrated that the

company had violated its permit on more than 1,000 days and that the violations

were “enormous.”

The court order called Formosa a “serial offender” who had “caused or contributed to the damages suffered by the recreational, aesthetic and economic value” of the area.

The court order called Formosa a “serial offender” who had “caused or contributed to the damages suffered by the recreational, aesthetic and economic value” of the area.

The parties entered

into settlement negotiations that were finalized on October 15. The agreement requires Formosa to pay $50 million over five years for mitigation

efforts to “provide environmental benefits to affected areas.” Formosa must

also engage engineers to design a system to halt the discharge of plastic

pellets and pay more the $3 million in attorneys’ fees.

Wilson and the San

Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper’s win is a small, but important, victory in

the fight against plastic pollution. Other environmental groups have already

taken notice and are making use of the citizen-suit provision:

The Southern Environmental Law Center recently filed its 60-day notice to sue Frontier Logistics, a pellet-packaging company, for plastic-pellet discharges into Cooper River in South Carolina.

The Southern Environmental Law Center recently filed its 60-day notice to sue Frontier Logistics, a pellet-packaging company, for plastic-pellet discharges into Cooper River in South Carolina.

In an era of decreased

regulation, citizen suits offer a promising way to reduce plastic pollution by

ensuring compliance with existing federal law. But public participation is also

key.

Citizen suits require citizen plaintiffs, and this victory wouldn’t have been achieved without Wilson and her efforts to document Formosa’s violations. As she told local media, “If we can do it, anybody can.” And thanks to her work, that next fight is already underway in South Carolina.

Citizen suits require citizen plaintiffs, and this victory wouldn’t have been achieved without Wilson and her efforts to document Formosa’s violations. As she told local media, “If we can do it, anybody can.” And thanks to her work, that next fight is already underway in South Carolina.

The opinions expressed

above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for

Biological Diversity or their employees.

Sarah J. Morath is a clinical associate professor at the

University of Houston Law Center. She writes about environmental, food, and

animal law and policy, and is currently writing Our Plastic Problem:

Costs and Solutions, forthcoming from Cambridge University Press in 2021.