EPA bans a pesticide widely used on food crops after 14 years of pressure from environmental and labor groups

Gina Solomon, University of California, San Francisco

|

| Chlorpyrifos is widely used on crops, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, corn and soybeans. AP Photo/John Raoux |

1. What is chlorpyrifos, and how is it used?

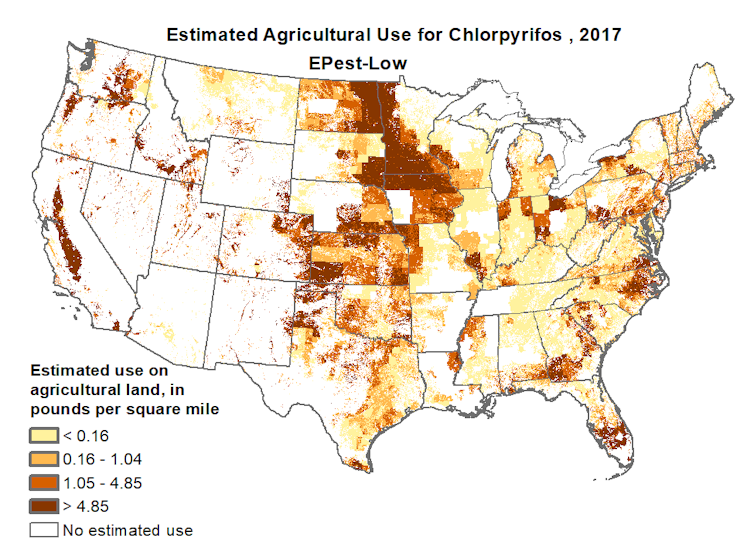

Chlorpyrifos is an inexpensive and effective pesticide that has been on the market since 1965. According to the EPA, approximately 5.1 million pounds of chlorpyrifos have been used annually in recent years (2014-2018) on a wide range of crops, including many different vegetables, corn, soybeans, cotton and fruit and nut trees.

Like other organophosphate insecticides, chlorpyrifos is designed to kill insects by blocking an enzyme called acetylcholinesterase. This enzyme normally breaks down acetylcholine, a chemical that the body uses to transmit nerve impulses. Blocking the enzyme causes insects to have convulsions and die. All organophosphate insecticides are also toxic and potentially lethal to humans.

Until 2000, chlorpyrifos was also used in homes for pest control. It was banned for indoor use after passage of the 1996 Food Quality Protection Act, which required additional protection of children’s health. Residues left after indoor use were quite high, and toddlers who crawled on the floor and put their hands in their mouth were found to be at risk of poisoning.

Despite the ban on household use and the fact that chlorpyrifos doesn’t linger in the body, over 75% of people in the U.S. still have traces of chlorpyrifos in their bodies, mostly due to residues on food. Higher exposures have been documented in farm workers and people who live or work near agricultural fields.

2. What’s the evidence that chlorpyrifos is harmful?

Researchers published the first study linking chlorpyrifos to potential developmental harm in children in 2003. They found that higher levels of a chlorpyrifos metabolite – a substance produced when the body breaks down the pesticide – in umbilical cord blood were significantly associated with smaller infant birth weight and length.

Subsequent studies published from 2006 to 2014 showed that those same infants had developmental delays that persisted into childhood, with lower scores on standard tests of development and changes that researchers could see on MRI scans of the children’s brains. Scientists also discovered that a genetic subtype of a common metabolic enzyme in pregnant women increased the likelihood that their children would experience neurodevelopmental delays.

These findings touched off a battle to protect children from chlorpyrifos. Some scientists were skeptical of results from epidemiological studies that followed the children of pregnant women with greater or lesser levels of chlorpyrifos in their urine or cord blood and looked for adverse effects.

Epidemiological studies can provide powerful evidence that something is harmful to humans, but results can also be muddled by gaps in information about the timing and level of exposures. They also can be complicated by exposures to other harmful substances through diet, personal habits, homes, communities and workplaces.

|

| Farm laborers, like these workers harvesting curly mustard in Ventura County, Calif., are especially vulnerable to pesticide exposure. Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images |

3. Why did it take so long to reach a conclusion?

As evidence accumulated that low levels of chlorpyrifos were probably toxic to humans, regulatory scientists at the EPA and in California reviewed it – but they took very different paths.

At first, both groups focused on the established toxicity mechanism: acetylcholinesterase inhibition. They reasoned that preventing significant disruption of this key enzyme would protect people from any other neurological effects.

Scientists working under contract for Dow Chemical, which manufactured chlorpyrifos, published a complex model in 2014 to estimate how much of the pesticide a person would have to consume or inhale to trigger acetylcholinesterase inhibition. But some of their equations were based on data from as few as six healthy adults who had swallowed capsules of chlorpyrifos during experiments in the 1970s and early 1980s – a research method that now would be considered unethical.

California scientists questioned whether risk assessments based on the Dow-funded model adequately accounted for uncertainty and human variability. They also wondered whether acetylcholinesterase inhibition was really the most sensitive biological effect.

In 2016 the EPA released a reassessment of chlorpyrifos’s potential health effects that took a very different approach. It focused on epidemiological studies published from 2003 through 2014 at Columbia University that found developmental impacts in children exposed to chlorpyrifos. The Columbia researchers analyzed chlorpyrifos levels in the umbilical cord blood at birth, and the EPA attempted to back-calculate how much chlorpyrifos the babies might have been exposed to throughout pregnancy.

On the basis of this analysis, the Obama administration concluded that chlorpyrifos could not be safely used and should be banned. However, the Trump administration halted this decision one year later, arguing that the science was not resolved and more study was needed. The Trump administration subsequently abandoned the human epidemiological studies and reverted to using the Dow-sponsored model and acetylcholinesterase inhibition endpoint that was used back in 2014.

History indicates that both political and scientific considerations likely accounted for the long delays. Although the conclusions clearly shifted with different federal administrations, the epidemiological studies and the acetylcholinesterase model also pointed in different directions – one suggested high health risks in humans, and the other suggested relatively lower risks. Policy conclusions thus depended partly on which data scientists chose as the basis for evaluating health risks.

4. What convinced California to impose a ban?

Three new papers on prenatal exposures to chlorpyrifos, published in 2017 and 2018, broke the logjam. These were independent studies, conducted on rats, that evaluated subtle effects on learning and development.

The results were consistent and clear: Chlorpyrifos caused decreased learning, hyperactivity and anxiety in rat pups at doses lower than those that affected acetylcholinesterase. And these studies clearly quantified doses to the rats, so there was no uncertainty about their exposure levels during pregnancy. The results were eerily similar to effects seen in human epidemiological studies, vindicating serious health concerns about chlorpyrifos.

California reassessed chlorpyrifos, using these new studies. Regulators concluded that the pesticide posed significant risks that could not be mitigated, especially among people who lived near agricultural fields where it was used. In October 2019, the state announced that under an enforceable agreement with manufacturers, all sales of chlorpyrifos to California growers would end by Feb. 6, 2020, and growers would not be allowed to possess or use it after Dec. 31, 2020.

Two months after the California decision, the European Union voted to ban chlorpyrifos due to concerns about neurodevelopmental harm. New York, Hawaii, Oregon and Maryland also moved to end use of the pesticide within their borders. On the same day that California sales of the pesticide ceased, the main manufacturer of chlorpyrifos, Corteva Agrosciences, announced that it would stop producing the chemical.

5. Why is the EPA acting now?

This saga began in 2007, when the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Pesticide Action Network formally petitioned the EPA to ban chlorpyrifos, citing epidemiological evidence that the chemical caused harm to brain development. (I worked at NRDC at the time and reviewed scientific studies on chlorpyrifos, but was not directly involved with the petition.)

Over a decade passed while the agency reevaluated the science, studying multiple ways of analyzing the data. In 2016 the EPA proposed to grant the petition and ban chlorpyrifos, but did not complete this action by the end of the Obama administration.

In July 2019, under the Trump administration, the EPA denied the petition, saying that claims about neurodevelopmental toxicity were “not supported by valid, complete and reliable evidence.” Nonetheless, a new EPA risk assessment released in 2020 identified significant risks associated with combined exposures to chlorpyrifos from multiple sources, including food and drinking water.

In late April 2021, a federal court in California ordered the agency to either ban use of chlorpyrifos on food within 60 days or show that it was safe. “The EPA has had nearly 14 years to publish a legally sufficient response to the 2007 Petition,” the ruling stated. “During that time, the EPA’s egregious delay exposed a generation of American children to unsafe levels of chlorpyrifos.”

With the agency’s Aug. 18 announcement, that delay is finally over.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Jan. 23, 2020.![]()

Gina Solomon, Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.