By FRANK CARINI/ecoRI News staff

Pesticides can be

beneficial, but lackadaisical monitoring and the misuse of labeling

instructions can lead to overuse and environmental accumulation

During the past seven

years the Rhode Island Department of Transportation has applied at least 43,959

gallons of herbicide, diluted by water at various ratios, to public lands

across the state, according to agency documents.

In early September,

ecoRI News filed an open records request with the Department of Transportation

(DOT) asking for the amount of pesticide the state agency has applied since

2011.

The agency only applies herbicides, according to a DOT spokesman. The request was answered promptly, but the “spraying logs” for 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 reveal a haphazard approach to documenting what is being sprayed where and why.

The agency only applies herbicides, according to a DOT spokesman. The request was answered promptly, but the “spraying logs” for 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 reveal a haphazard approach to documenting what is being sprayed where and why.

For instance, these

spraying logs seldom note what targeted plants are being poisoned by what

herbicide. The information provided often noted how many diluted gallons were

applied, but not the herbicide used.

Other times, the herbicide applied is noted, but not the amount of gallons sprayed. In fact, the amount and type of herbicide used is routinely absent. The documentation provided to ecoRI News makes it difficult to discern if label instructions were followed.

Other times, the herbicide applied is noted, but not the amount of gallons sprayed. In fact, the amount and type of herbicide used is routinely absent. The documentation provided to ecoRI News makes it difficult to discern if label instructions were followed.

The DOT, typically using

truck-mounted hand-sprayers, annually treats “problem areas” along Rhode

Island’s 1,100 miles of state roads, highways and bridges with herbicides.

These chemicals are applied to sidewalks, guardrails, shoulders and curbs, along high-speed barriers, and around power lines, to prevent the growth of troublesome species such as bamboo, poison ivy and Japanese knotweed.

These chemicals are applied to sidewalks, guardrails, shoulders and curbs, along high-speed barriers, and around power lines, to prevent the growth of troublesome species such as bamboo, poison ivy and Japanese knotweed.

The herbicide dicamba, under the commercial name Vanquish, is used regularly, according to DOT documents. Nufarm, the Australia-based agricultural chemical company that makes the product, claims, “Vanquish offers superb control of over 200 broadleaf weeds, brush, and vine species and is also an ideal tank-mix partner for even more comprehensive vegetation control.”

The company also notes

that, “After application, the active ingredient Dicamba is easily absorbed

through the leaf surface and the translocates throughout the plant causing the

weed to collapse.”

Vanquish is just one of about 400 products that contain dicamba. The benzoic acid is on the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s list of restricted-use pesticides, meaning it’s more highly regulated and requires training to apply.

DEM’s list is based upon

the Restricted Use Products Report database

maintained by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Manufacturers are required to register their pesticides annually with DEM before the products can be sold or used in the state.

Pesticides used in Rhode Island fall into two categories: restricted use and general use. General-use pesticides can be purchased over the counter and require no level of training.

Manufacturers are required to register their pesticides annually with DEM before the products can be sold or used in the state.

Pesticides used in Rhode Island fall into two categories: restricted use and general use. General-use pesticides can be purchased over the counter and require no level of training.

Howard Cook, DEM’s

pesticides supervisor, told ecoRI News there are between 7,000 and 9,000

pesticides registered in the state annually.

Dicamba, which was

registered with the EPA in 1967, mimics the plant hormone auxin, causing

uncontrolled growth that eventually kills the plant.

It’s meant for post-emergent plant control. It’s highly mobile in soil and may contaminate groundwater. Its leaching potential increases with precipitation and amount applied.

It’s meant for post-emergent plant control. It’s highly mobile in soil and may contaminate groundwater. Its leaching potential increases with precipitation and amount applied.

The herbicide is harmful

to aquatic organisms, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The EPA doesn’t classify dicamba as a human carcinogen.

This past summer,

however, the EPA reported that

some states were reporting high numbers of agricultural complaints related to

dicamba.

“By early July, we

already had reports of hundreds of complaints received by state agencies in

Arkansas, Missouri and Tennessee (a significant increase from last year),”

according to the EPA. “Both physical drift and volatilization of dicamba from

the target application site have been reported.”

The herbicide

glyphosate, under the commercial name Razor, is also used

regularly by DOT.

Glyphosate is the most common herbicide in the United States — some 750 products containing glyphosate are sold here — and was popularized as the main ingredient in Monsanto’s herbicide products called Roundup, which the DOT also uses, according to spraying log documentation.

Glyphosate is the most common herbicide in the United States — some 750 products containing glyphosate are sold here — and was popularized as the main ingredient in Monsanto’s herbicide products called Roundup, which the DOT also uses, according to spraying log documentation.

Nufarm, which also manufactures Razor, says this herbicide

is “for broad-spectrum control of hard-to-kill weeds.” The company also claims

that glyphosate, the active ingredient in Razor, “is one of the most trusted

and proven herbicides available.”

Glyphosate, however, poses a broader range of

health risks than dicamba.

Research has shown that the chemical, first registered for use in the United States in 1974, is an endocrine (hormonal) disruptor. A 2015 study by the World Health Organization’s cancer agency found that it was “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

Since classifying glyphosate as a probable carcinogen, the international agency has had to defend itself from attacks aimed at undermining its credibility.

Research has shown that the chemical, first registered for use in the United States in 1974, is an endocrine (hormonal) disruptor. A 2015 study by the World Health Organization’s cancer agency found that it was “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

Since classifying glyphosate as a probable carcinogen, the international agency has had to defend itself from attacks aimed at undermining its credibility.

The mass spraying of

glyphosate-based herbicides also has led to an explosion of resistant weeds,

which have evolved to survive despite being sprayed, according to a 2016 study.

Besides being the top

herbicide sold in the United States, it’s also commonly used in Europe. In

fact, a recent story in The Guardian reported

that its use is so pervasive that its residues were found in 45 percent

of Europe's topsoil, and in

the urine of three-quarters of Germans tested.

Glyphosate residues also have been found in biscuits, crackers and breakfast cereals, and in 60 percent of breads sold in the United Kingdom.

Glyphosate residues also have been found in biscuits, crackers and breakfast cereals, and in 60 percent of breads sold in the United Kingdom.

Since glyphosate was

introduced four decades ago, enough of this enzyme-blocking herbicide has

been applied worldwide to

cover every cultivated acre of land in the world with a half-pound of this

poison.

The EPA says prolonged

exposure to glyphosates in drinking water can lead to kidney and reproductive

difficulties.

Weeding and mowing are

alternatives to control nuisance plant species, but herbicides, such as

Vanquish, Razor and Roundup, are inexpensive alternatives. Vanquish costs about

$60 for a gallon of concentrate. Razor is even less expensive, at about $55 for

a 2.5-gallon jug of concentrate.

During the past seven

years, DOT has spent at least $13,492 on herbicides, according to documentation

provided by the state agency. ecoRI News submitted a second open records

request with DOT asking the agency how much it has spent annually on such products

since 2011.

The eight pdf files

e-mailed to ecoRI News don’t seem to tell the complete story. The documentation

included a duplicate herbicide receipt, and receipts for wildflower seed mix,

salt-tolerant seed mix, and a 50-pound bag of mulch. Also, herbicide receipts

were only provided for three — 2011, 2012 and 2013 — of the seven years

requested. It’s possible DOT hasn’t bought any herbicide since 2013.

DOT wouldn’t make anyone

available for an interview.

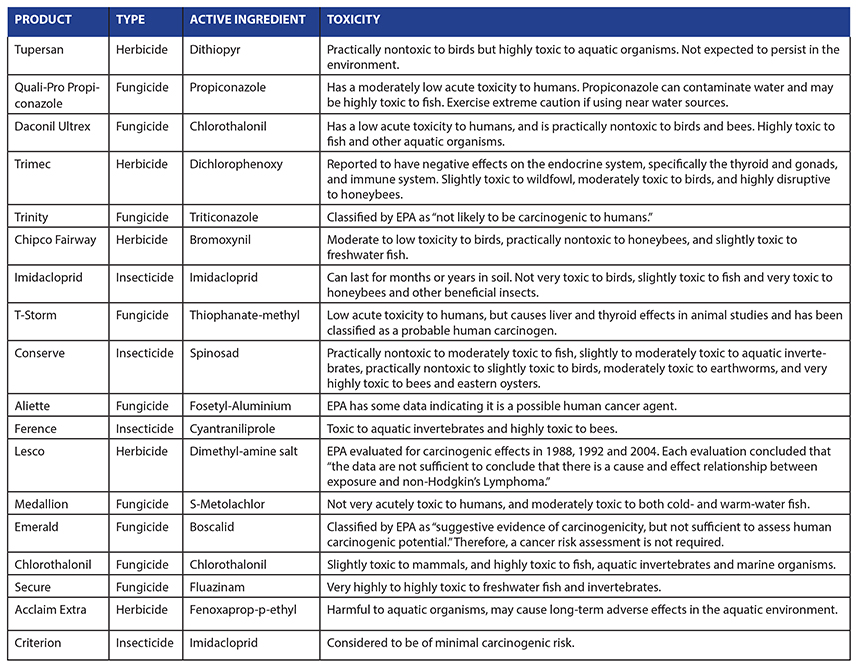

A total of 18

pesticides, in various diluted ratios, were applied to the public golf course

at Goddard Memorial State Park in Warwick, R.I., this year. (ecoRI News

graphic)

Managing the environment

with chemicals

Pesticides are also applied at state parks, to the Statehouse grounds, and on other state-managed lands. Each of Rhode Island’s 39 cities and towns also apply poisons to eliminate unwanted plants and insects from public property.

In early October, for

instance, DEM treated Carolina Trout Pond in Richmond with Reward, to “help

control invasive weeds” such as watermilfoil and water hyacinth.

In a Sept. 28 DEM press release announcing the

October applications of the poison, the state agency doesn’t mention the

herbicide that will be used, just that, “The chemical treatment, which will be

applied two times this fall, poses no public health risk nor harm to fish or

other aquatic life.”

ecoRI News found out,

through a DEM spokeswoman, what herbicide was applied.

The active ingredient

in Reward is diquat

dibromide, a plant growth regulator. It’s a quick-acting contact herbicide.

But, like many pesticides, it’s nonselective, meaning that it doesn’t spare

non-target species from its effects.

Diquat dibromide is referred to as a

desiccant, because it causes an entire plant to dry out quickly. It’s not

residual, which means it doesn’t leave any trace on or in plants, soil or

water.

The herbicide is a moderately toxic chemical,

according to the Pesticide Information Project of Cooperative Extension Offices

of Cornell University, Michigan State University, Oregon State University and

the University of California.

It may be fatal to humans if swallowed, inhaled or absorbed through the skin. Concentrated solutions may cause severe irritation of the mouth, throat, esophagus and stomach, followed by nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, severe drying out of bodily tissues, gastrointestinal discomfort, chest pain, diarrhea, kidney failure, and toxic liver damage.

It may be fatal to humans if swallowed, inhaled or absorbed through the skin. Concentrated solutions may cause severe irritation of the mouth, throat, esophagus and stomach, followed by nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, severe drying out of bodily tissues, gastrointestinal discomfort, chest pain, diarrhea, kidney failure, and toxic liver damage.

DEM’s Sept. 28 press

release advised the public to avoid fishing and other recreational activities

in the pond on treatment days, and noted that signs “are posted around the pond

with information about temporary water use restrictions.”

Diquat dibromide ranges

from moderately toxic to practically nontoxic to birds, and is slightly toxic

to fish — “Its toxicity to fish, and food organisms on which fish survive, has

been reported in many studies” — according to the Pesticide Information Project.

DEM also applied Reward

to Peck Pond in Pascaog this year, for

needed weed control in a swimming area at Pulaski State Park and Recreational

Area. The herbicide was applied to kill northern milfoil, ribbon-leaf pondweed,

common bladderwort, yellow water lily, and white water lily.

In early September,

ecoRI News filed an open records request with DEM asking: What state properties

do DEM staff apply pesticides?; What type of pesticides are applied?; and How

much is applied annually to these properties? This request also was answered promptly.

The files furnished by DEM provided far better documentation than those of DOT.

ecoRI News was better able to confirm that label instructions were followed.

The documents showed

that during the past several years, DEM has applied a variety of pesticides to

Rhode Island waterbodies and public lands. For example, the golf course

at Goddard Memorial State Park — a nearly

500-acre park along the shores of Greenwich Cove and Greenwich Bay in Warwick —

was sprayed with nine different fungicides, five kinds of herbicides, and four

types of insecticides this year alone.

The 18 poisons were

applied to fairways, greens, tees, and aprons to kill crabgrass, stinkhorns,

broadleaf weeds, patch disease, grubs, goosegrass, and leaf and dollar spot.

The active ingredient, chlorothalonil, in one of the fungicides used this year

on the public golf course is on DEM’s list of restricted-use pesticides.

During the past two

years, a total of 28.5 gallons of poison has been applied in three state management areas — the Great Swamp

Management Area, the South Shore Management Area and the Big River Management

Area.

Razor, Garlon 3A, Pathfinder II, Roundup, and Gly Pho-Sel were used to kill broadleaf weeds and woody shrubs. Gly Pho-Sel — its active ingredient is glyphosate — was also been used in Colt State Park in Bristol and along the East Bay Bike Path during the past few years.

Razor, Garlon 3A, Pathfinder II, Roundup, and Gly Pho-Sel were used to kill broadleaf weeds and woody shrubs. Gly Pho-Sel — its active ingredient is glyphosate — was also been used in Colt State Park in Bristol and along the East Bay Bike Path during the past few years.

In 2015, between May 30

and Sept. 16, 6.7 gallons of Roundup were applied at Fort Adams State Park in Newport. Roundup

also has been used in the past few years in Lincoln Woods and along the Blackstone

River Bikeway.

At Fort Adams State

Park, throughout spring and summer 2015, 48 ounces of Brushmaster also

was applied. The active ingredient in this herbicide is 2,4-D, which is reported to have negative

effects on human endocrine and immune systems. It has been in pre-special

review status by the EPA since 1986, because of carcinogenicity concerns.

The Natural Resources

Defense Council (NRDC) calls 2,4-D The Most Dangerous Pesticide You’ve

Never Heard Of. It goes by various names and is in various products,

and is used on public lands in Rhode Island, according to the documentation

ecoRI News recently reviewed.

The International Agency for Research

on Cancer, in 2015, declared 2,4-D a possible human carcinogen.

Last year DEM approved

the application of 28.5 tons and 455.3 gallons of chemicals to waterbodies from Barrington to Westerly.

Most of that tonnage (28.3) came in the form of copper sulfate crystal, which the Newport Water Department and the Stone Bridge Fire District use as an algaecide in ponds, such Gardiner Pond in Middletown, North Easton Pond in Newport, St. Mary’s Pond in Portsmouth and Stafford Pond in Tiverton, that serve as public drinking-water supplies.

Most of that tonnage (28.3) came in the form of copper sulfate crystal, which the Newport Water Department and the Stone Bridge Fire District use as an algaecide in ponds, such Gardiner Pond in Middletown, North Easton Pond in Newport, St. Mary’s Pond in Portsmouth and Stafford Pond in Tiverton, that serve as public drinking-water supplies.

Copper sulfate crystals aren’t

typically dumped all at once. For example, it took eight applications for the

16,750 pounds of crystal to be applied to North Easton Pond. The active

ingredient in copper sulfate crystal is copper sulfate pentahydrate.

The EPA limit for copper

sulfate in drinking water is 1 parts per million. This limit was set to prevent

a disagreeable taste from copper in drinking water and to provide adequate

protection from toxicity, according to the Pesticide Information Project.

ecoRI News, for a September story, asked

DOT and DEM about the amount and kinds of pesticides applied annually to Rhode

Island public property. Neither state agency knows how much taxpayer-funded

pesticide is being applied to public lands. That lack of knowledge led to this

story.

For that first story, a

DOT spokesman said, “We do track, when, where and the amounts of herbicides

sprayed per DEM requirements. But our record keeping is paper based and while

we are working on building a central electronic record of this information, it

doesn’t exist yet. You would need to submit an access to public records act

request for the records or perhaps reach out to DEM.”

A DEM spokeswoman said,

“These records are reviewed periodically by DEM’s Division of Agriculture

during routine use and records inspections. DEM does not have comprehensive

information on the total quantities applied on public lands. The Department has

a record of applications made during the past year to waterbodies (ponds, lakes

and streams) that require an aquatic nuisance application and permit.”

Rush to poison

Last year the NRDC, after several years examining federal government data and interviewing officials, determined that the government has allowed the majority of pesticides onto the market without a full set of toxicity tests, using a loophole called a conditional registration. In fact, as many as 65 percent of more than 16,000 pesticides have been approved using this loophole.

Counting farmers and

exterminators, about a billion pounds of pesticides are used annually in the

United States to eliminate species deemed problematic, according to Beyond

Pesticides.

Many pesticides contain

persistent organic pollutants, which persist in the environment and accumulate

in the fatty tissue of humans and wildlife. This accumulation of toxins can

pose serious health risks, and has been linked to cancer, hormonal imbalances,

and birth defects.

Pesticides that are known to be persistent organic pollutants include aldrin, chlordane, dioxins, and DDT. Chlordane is on Rhode Island’s list of restricted-use pesticides.

Pesticides that are known to be persistent organic pollutants include aldrin, chlordane, dioxins, and DDT. Chlordane is on Rhode Island’s list of restricted-use pesticides.

Pesticides are

classified according to various criteria, including their chemical composition

and what organisms they target.

While herbicides, insecticides, algaecides, and fungicides can selectively target species, they don’t discriminate against what they kill, meaning, for example, insecticides also kill pollinators and other beneficial insects.

While herbicides, insecticides, algaecides, and fungicides can selectively target species, they don’t discriminate against what they kill, meaning, for example, insecticides also kill pollinators and other beneficial insects.

But the indiscriminate nature

of pesticides doesn’t stop there.

Animals higher up the food chain can suffer secondary poisoning, sometimes with fatal consequences, after consuming poisoned prey.

Animals higher up the food chain can suffer secondary poisoning, sometimes with fatal consequences, after consuming poisoned prey.

Much of Rhode Island’s

public lands, and waters, are treated with pesticide, often with more than one

— see, golf course at Goddard Memorial State Park.

No one knows — nor has it been studied — how all these different pesticides unleashed on the environment interact with each other, or how they mix with sunlight, water, and other organic and inorganic chemicals, and what combined impact this is having on human health and ecosystems.

No one knows — nor has it been studied — how all these different pesticides unleashed on the environment interact with each other, or how they mix with sunlight, water, and other organic and inorganic chemicals, and what combined impact this is having on human health and ecosystems.

Common sense dictates

overreliance on pesticides has already or will come with consequences.