So, of course, Trump-Musk is eliminating the program

NASA

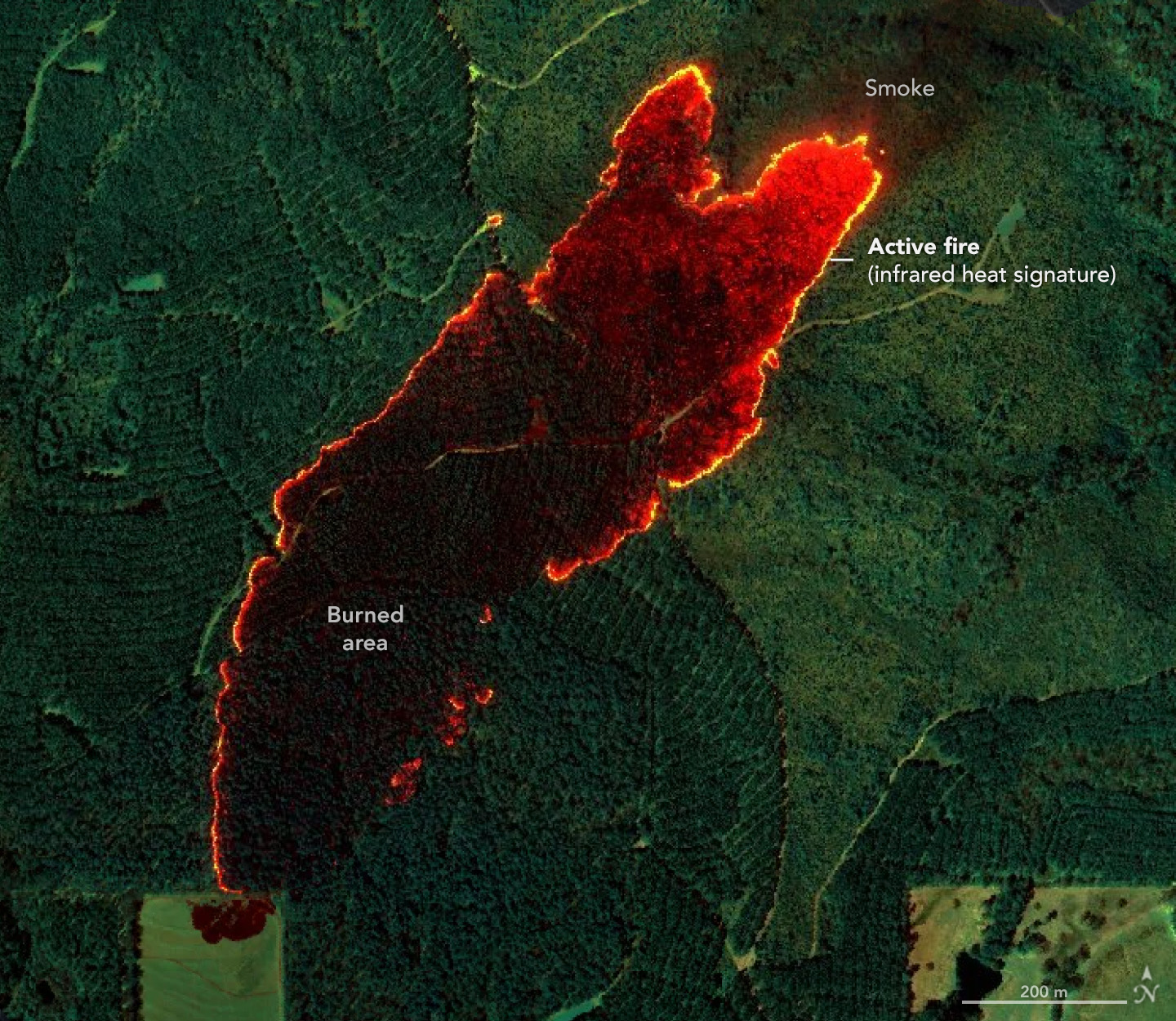

A NASA sensor recently brought a new approach to battling wildfire, providing real-time data that helped firefighters in the field contain a blaze in Alabama. Called AVIRIS-3 (Airborne Visible Infrared Imaging Spectrometer 3), the instrument detected a 120-acre fire on March 19 that had not yet been reported to officials.As AVIRIS-3 flew aboard a King Air B200 research plane over

the fire about 3 miles (5 kilometers) east of Castleberry, Alabama, a scientist

on the plane analyzed the data in real time and identified where the blaze was

burning most intensely. The information was then sent via satellite internet to

fire officials and researchers on the ground, who distributed images showing

the fire’s perimeter to firefighters’ phones in the field.

All told, the process from detection during the flyover to

alert on handheld devices took a few minutes. In addition to pinpointing the

location and extent of the fire, the data showed firefighters its perimeter,

helping them gauge whether it was likely to spread and decide where to add

personnel and equipment.

EDITOR'S NOTE: On the same day NASA released this story, NBC News that NASA budget cuts put wildfire fighting programs at risk. Staff firings, budget cuts and grant suspensions at all federal agencies that help state and local firefighters are being chain-sawed to death by Musk and Trump for reasons that beggar justification. States don't have their own satellites, but maybe the answer lies with the fact that Elon Musk does - and the hidden agenda is to force states to pay SpaceX to get data that NASA has been supplying. - Will Collette

“This is very agile science,” said Robert Green, the AVIRIS

program’s principal investigator and a senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet

Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), noting AVIRIS-3 mapped the burn

scar left near JPL by the Eaton Fire in January. The AVIRIS-3 sensor

belongs to a line of imaging spectrometers built at JPL since 1986. The

instruments have been used to study a wide range of phenomena—including fire—by

measuring sunlight reflecting from the planet’s surface.

March 21, 2025JPEG

Observing the ground from about 9,000 feet (3,000 meters) in

altitude, AVIRIS-3 flew aboard several test flights over Alabama, Mississippi,

Florida, and Texas for the NASA 2025

FireSense Airborne Campaign. Researchers flew in the second half of March

to prepare for prescribed burn experiments that took place in the Geneva State

Forest in Alabama on March 28 and at Fort Stewart-Hunter Army Airfield in

Georgia from April 14 to 20. During the March span, the AVIRIS-3 team mapped at

least 13 wildfires and prescribed burns, as well as dozens of small hot spots

(places where heat is especially intense)—all in real time.

For the Castleberry Fire, shown at the top of this page on

March 19, 2025, having a clear picture of where it was burning most intensely

enabled firefighters to focus on where they could make a difference—on the

northeastern edge.

Then, two days after identifying Castleberry Fire hot spots,

the sensor spotted a fire about 4 miles (2.5 kilometers) southwest of Perdido,

Alabama (above). As forestry officials worked to prevent flames from reaching

six nearby buildings, they noticed that the fire’s main hot spot was inside the

perimeter and contained. With that intelligence, they decided to shift some

resources to fires 25 miles (40 kilometers) away near Mount Vernon, Alabama.

To combat one of the Mount Vernon fires (below), crews used

AVIRIS-3 maps to determine where to establish fire breaks beyond the

northwestern end of the fire. They ultimately cut the blaze off within about

100 feet (30 meters) of four buildings.

March 21, 2025JPEG

During the March flights, researchers created three types of

maps, which are shown above for the Perdido and Mount Vernon fires. One, called

the Fire Quicklook (left), combines brightness measurements at three

wavelengths of infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye, to identify

the relative intensity of burning. Orange and red areas on the Fire Quicklook

map show cooler-burning areas, while yellow indicates the most intense flames.

Previously burned areas show up as dark red or brown.

Another map type, the Fire 2400 nm Quicklook (middle), looks

solely at infrared light at a wavelength of 2,400 nanometers. The images are

particularly useful for seeing hot spots and the perimeters of fires, which

show brightly against a red background. A third type of map (right), called

just Quicklook, shows burned areas and smoke.

The Fire 2400 nm Quicklook was the “fan favorite” among the

fire crews, said Ethan Barrett, fire analyst for the Forest Protection Division

of the Alabama Forestry Commission. Seeing the outline of a wildfire from above

helped Alabama Forestry Commission firefighters determine where to send

bulldozers to stop the spread.

Additionally, FireSense personnel analyzed the AVIRIS-3

imagery to create digitized perimeters of the fires. This provided firefighters

with fast, comprehensive intelligence of the situation on the ground.

Data from imaging spectrometers like AVIRIS-3 typically

takes days or weeks to be processed into highly detailed, multilayer image

products used for research. By simplifying the calibration algorithms,

researchers were able to process data on a computer aboard the plane in a

fraction of the time it otherwise would have taken. Airborne satellite internet

connectivity enabled the images to be distributed almost immediately, while the

plane was still in flight, rather than after it landed.

“Fire moves a lot faster than a bulldozer, so we have to try

to get around it before it overtakes us. These maps show us the hot spots,”

Barrett said. “When I get out of the truck, I can say, ‘OK, here’s the

perimeter.’ That puts me light-years ahead.”

AVIRIS and the FireSense Airborne Campaign are part of

NASA’s work to leverage its expertise with airborne technologies to combat

wildfires. The agency also recently demonstrated

a prototype from its Advanced Capabilities for Emergency Response

Operations project that will provide reliable airspace management for drones

and other aircraft operating in the air above wildfires.

NASA Earth Observatory images annotated by Lauren Dauphin

using AVIRIS-3 data via

the AVIRIS

Data Portal. Story by Andrew Wang, adapted for NASA Earth Observatory.

NASA budget cuts put wildfire fighting programs at risk

The FireSense project uses controlled burns to study how

wildfires spread, and it could help prevent them before they happen.

v

NASA scientists study a prescribed burn at Fort Stewart,

Ga., on April 14.Milan P. Loiacono / NASA

- Savewith

a NBCUniversal Profile

Create your free profile or log in to save this article

April 30, 2025, 10:00 AM EDT

By Denise Chow and Jacob

Soboroff

HINESVILLE, Ga. — From an altitude of 9,000 feet, NASA

scientists soared over hundreds of acres of burning brush this month at Fort

Stewart Army base, monitoring the flames as they spread and engulfed the land.

This time, the blaze was a controlled one, set intentionally

to clear the area in what’s known as a “prescribed burn.” But the research,

which makes up NASA’s FireSense project, will help firefighters battle real

wildfires when they do ignite, and it could even help land managers prevent

some blazes from starting in the first place.

Yet with the Trump administration reportedly proposing steep

budget cuts at NASA and other federal agencies, programs like FireSense could

be in jeopardy — all while fire season is ramping up.

Last year, wildfires scorched nearly 9 million acres in the

United States, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. The agency’s annual

report found that the number of wildfires reported in 2024 and the acres burned

were both “noticeably higher than the five and 10-year averages.”

0 seconds of 3 minutes, 5 secondsVolume 90%

How

NASA is helping first responders combat wildfires

03:05

Studies have shown that climate change is not only making

wildfires more frequent but also intensifying the blazes that do ignite, making

them more destructive.

“The problem is getting worse,” said Michele Steinberg,

wildfire division director at the nonprofit National Fire Protection

Association. “We are seeing more fires in areas we don’t normally see them and

in seasons we don’t expect them. We’re seeing fires burning hotter and more

intensely, and when you get just the right conditions, they can move very

fast.”

The extreme fires pose enormous health, financial and

environmental risks, which make studying them crucial for protecting lives and

livelihoods.

NASA is hardly alone in focusing its attention on wildfires.

The U.S. Forest Service, the Interior Department and the Bureau of Land

Management are some of the key federal agencies involved with wildfire response

and prevention. But what the space agency is doing differently is applying

advanced technologies — including some that are similarly used for satellites

in space — to fill gaps in knowledge.

“FireSense was born because NASA said: Wildfires are a big

and emerging problem, and we’re going to invest and we’re going to use our

skill set to help the rest of the government do its job better,” said Michael

Wara, a lawyer and senior research scholar at Stanford University who

specializes in climate and energy policy.

The project’s scientists work with local, state and federal

agencies — as well as partners in academia — to better understand fire behavior

and intensity, air quality concerns during and after wildfires and how

ecosystems recover following blazes. The researchers are also studying how to

manage vegetation in vulnerable areas to lower the risk of wildfires or halt

their rapid spread.

“The goal is to take our innovative technology, go into the

field with wildland fire managers and actually transfer that innovative

technology so that they can use it on a wildland fire,” said Jacquelyn Shuman,

the project scientist for NASA FireSense.

The project uses an instrument known as a spectrometer that

is the same design as one that operates in low-Earth orbit aboard the

International Space Station. It’s that technology that can provide detailed and

precise measurements that help firefighters and land managers before, during

and after extreme fires.

At Fort Stewart, the scientists flew over the prescribed

burn, watching its movement and mapping the blaze using a sophisticated

infrared instrument known as AVIRIS-3 (short for Airborne Visible and InfraRed

Imaging Spectrometer 3). The fire would eventually engulf around 700 acres.

NASA scientists study a prescribed

burn at Fort Stewart on April 14.Milan P. Loiacono / NASA

They paid particular attention to how fast the fire was

spreading, where it was gaining ground and how hot it was.

Prescribed burns are fires that are intentionally set to

manage ecosystems that need periodic fires to stay healthy. They are also

carried out to reduce the amount of dry and flammable vegetation that could

easily catch flame.

The burns are carefully planned and executed under specific

weather conditions to maintain control over their spread, but those practices

also function as science experiments for wildfire researchers, said Harrison

Raine, a former elite firefighter who now works as a project coordinator for

FireSense.