By MICHAEL LOMBARDI/ecoRI News

contributor

|

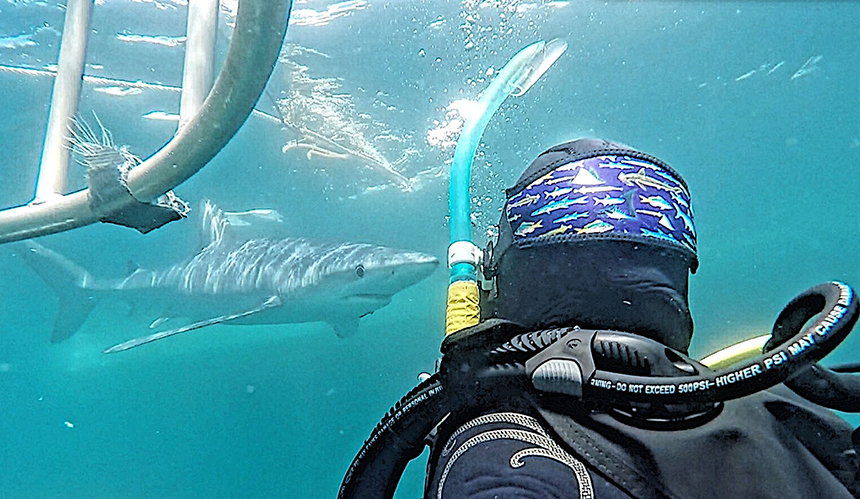

| Blue sharks will cruise right along the water’s surface and nose in to the camera for a photo. |

Our little Ocean State stakes its

claim in many seasonal summertime favorites: coffee ice cream, a trip to Salty

Brine Beach, Del’s Lemonade, Bristol’s Fourth of July parade, fried clams, a

sail around Newport, great outdoor concerts, McCoy Stadium fireworks, a ferry

ride to Block Island, and …

That list can go on and on, making

Rhode Island just as much a summertime travel destination as it is a true

cultural gem for we residents.

There’s much more to the Ocean

State, however, and it shouldn’t be with any irony that, well, there’s some

magic happening underwater just off our shores.

I’ve been diving in Rhode Island for

more than 20 years, and I’m still in awe of the spectacular sites, wildlife

interactions, and untapped exploration that is right here in our backyard.

We have World War II shipwreck graveyards, artificial reefs, several gamefish species for harvesting or spearfishing, and the blue shark.

We have World War II shipwreck graveyards, artificial reefs, several gamefish species for harvesting or spearfishing, and the blue shark.

My first foray 20-30 miles offshore

of Rhode Island to explore our blue shark population was in 2008, where I

documented the experience for Rhode Island

Monthly.

While the experience is accessible for anyone with an interest and the ability to comfortably swim/snorkel in the ocean, it does take a bit of commitment to putting yourself out there on the edge, which certainly isn’t for everyone.

While the experience is accessible for anyone with an interest and the ability to comfortably swim/snorkel in the ocean, it does take a bit of commitment to putting yourself out there on the edge, which certainly isn’t for everyone.

The sharks’ translucent blue back

coloration is highly reflective off of the surface. This countershading makes

them difficult to see when hovering above them in deep water.

In the decade since that 2008

excursion, I’ve ventured offshore annually, making arrangements for educators,

students, and scientists to join in the full experience and interact with the blue shark, and it never gets old. I’ve been diving around the world —

Antarctica, Hong Kong, Bahamas, Solomon Islands — and yet remain completely in

awe with every journey offshore of the Ocean State.

It’s a 2-hour ride out from Point

Judith, which tends to be rather uneventful. We pass Block Island, the wind

farm, and when arriving on site we cut the engines, and drift.

The water is warm (65 degrees Fahrenheit), the seas are calm — though not always the case — and there is nothing but fresh ocean breeze in the air, until the chumming starts.

The water is warm (65 degrees Fahrenheit), the seas are calm — though not always the case — and there is nothing but fresh ocean breeze in the air, until the chumming starts.

First, we deploy a shark cage — a

protective enclosure constructed of welded aluminum bars that the divers can

enter if and when the sharks get a bit frisky, or if we encounter a more

aggressive species, such as the mako, or perhaps a white.

There is always chatter about a white shark encounter on the ride out as people share sea stories, but this is a rare occurrence in our waters. White sharks favor Cape Cod waters that harbor a healthy population of seals.

There is always chatter about a white shark encounter on the ride out as people share sea stories, but this is a rare occurrence in our waters. White sharks favor Cape Cod waters that harbor a healthy population of seals.

Then comes the chum, a mix of

slushy/frozen fish parts, mackerel bits, which have nice shiny and reflective

scales, and then a shot of mackerel oil. If you’re a bit queasy from

seasickness, the stench of concentrated fish oil doesn’t help.

Once the oil hits the water, the chum slick is quite visible at the water’s surface as we drift along, and wait, and drift, and wait.

Once the oil hits the water, the chum slick is quite visible at the water’s surface as we drift along, and wait, and drift, and wait.

Setting the stage at this point —

it’s a waiting game. We’re all eager to jump in the water, but at the same time

don’t want to scare away any early arrivers with our bubbles and clunky dive

gear.

So, the drill is to roast in the sun, snack on boat friendly food, potentially doze off for a short nap, tell fish stories, and otherwise stare out at the slick for a fin to break the surface indicating that our neighbors have arrived for a visit.

So, the drill is to roast in the sun, snack on boat friendly food, potentially doze off for a short nap, tell fish stories, and otherwise stare out at the slick for a fin to break the surface indicating that our neighbors have arrived for a visit.

Interactions outside of the cage are

engaging and memorable. Blue sharks aren't typically aggressive toward humans.

However, they can become frisky and the diver must use good judgment to make

use of the cage, or even exit the water.

Once the first shark is sighted near

the surface, it’s an all out frenzy on the boat. We scramble to put together

dive gear, ready our cameras, and work to overcome the inherent anxiety of

jumping in the water where a shark is just feet away.

Once in the water, that anxiety fades away as we encounter and interact with one of the most beautiful shark species — Prionace glauca, the blue shark.

Once in the water, that anxiety fades away as we encounter and interact with one of the most beautiful shark species — Prionace glauca, the blue shark.

“… this experience felt much more interactive. While I was observing the sharks around me, I felt as though they were also observing me. They were curious about our presence there and would get close to try to figure us out. In some other shark encounters I've had, the sharks would either ignore us, flee from us, or come expecting that we would feed them (as divers have done in the past at that specific location). With these blue sharks, it seemed different, as though they were genuinely curious about us in a non-aggressive way, trying to understand why we were there and what we were doing.”— Karina Scavo, Ph.D. candidate Boston University

So why blue sharks? Well, they are

perhaps the single most abundant and transient species in the world’s oceans.

Blues tagged here in New England have turned up in Europe, Africa, and the

Caribbean.

Unlike most species which are more or less geographically isolated, these sharks are truly ocean-going, making them one of the most influential animal species on this planet given their predatory nature.

In addition, these are among the most beautiful fish in the sea. The hues of blue across their backs that serve as camouflage in deep water can’t be replicated. It’s a blue that becomes “alive” as the sun strikes their back near the surface.

Unlike most species which are more or less geographically isolated, these sharks are truly ocean-going, making them one of the most influential animal species on this planet given their predatory nature.

In addition, these are among the most beautiful fish in the sea. The hues of blue across their backs that serve as camouflage in deep water can’t be replicated. It’s a blue that becomes “alive” as the sun strikes their back near the surface.

Many reading this and looking at the

images will be asking, “Aren’t you afraid of getting bit?” The answer is both

yes and no. Indeed, these are predatory animals in their natural habitat, not much

different than viewing a lion on a safari.

However, this species is largely benign to people — these aren’t the ferocious carnivores mistakenly portrayed in the movies. Blue sharks eat fish for the most part, and pose little risk to humans.

However, this species is largely benign to people — these aren’t the ferocious carnivores mistakenly portrayed in the movies. Blue sharks eat fish for the most part, and pose little risk to humans.

On the other hand, with so much food

(chum) in the water, it’s possible for accidents to happen, and little bumps

and nips — on fins or other loose gear — are not uncommon. In my experience,

they are as curious of us as we are of them, and the interaction commands a well-balanced

mutual respect.

An experimental ‘selfie’ using a

wide-angle virtual-reality camera. The sharks ended up biting at the camera, so

its use was aborted.

Each year, I work toward finding an

improved means to bring these blue shark interactions back to the terrestrial

community.

My mission for this summer’s excursion was an experiment with virtual-reality, 360-degree camera techniques.

Hours and hours of editing may or may not reveal “the shot,” but that’s the challenge in capturing these alien environments:

We have limited time offshore, even more limited time in the water, and very little effort can be placed on trial and error. So, any lessons learned this year, may not be reworked into the program until next year.

My mission for this summer’s excursion was an experiment with virtual-reality, 360-degree camera techniques.

Hours and hours of editing may or may not reveal “the shot,” but that’s the challenge in capturing these alien environments:

We have limited time offshore, even more limited time in the water, and very little effort can be placed on trial and error. So, any lessons learned this year, may not be reworked into the program until next year.

“This close-up interaction gave us an even deeper appreciation for the role that these sharks play in our ocean world. Many people think that they are bloodthirsty man-eaters, but a couple hours of swimming with them would demonstrate to even the most skeptical person that they have been historically mislabeled, which has potentially lead to their overfishing and poor treatment via finning. They are beautiful creatures that serve as apex predators, controlling top-down ecosystem processes, but are also very charismatic, and many would be surprised to learn that they live in offshore waters so close to New England, both good reasons to increase local and global protections for them.”— Katey Lesneski, Ph.D. candidate, Boston University

We did learn one useful lesson

within just minutes of the blue sharks arriving: the electrical noise coming

from the small VR camera is rather attractive to the sharks, and that led to a

few aggressive bumps and nips on the camera.

Fortunately, the equipment was

spared, but it meant putting the system away until we develop a better means to

protect it.

As visually striking as the sharks

are, after an hour or two swimming with them, it’s easy to be overcome with some

humbling sadness. Call it the “Summertime Blues.”

With a little research, one will learn that these blue sharks are significantly overfished. Being transient, they are caught in all of the world’s oceans, primarily as by-catch, but also for select Asian markets.

With a little research, one will learn that these blue sharks are significantly overfished. Being transient, they are caught in all of the world’s oceans, primarily as by-catch, but also for select Asian markets.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species classifies blues as “near threatened,” with an

estimated 20 million sharks caught and killed annually. It doesn’t take an

advanced degree in science to recognize that this isn’t sustainable.

The gap in human knowledge and

understanding, as I see it, is recognizing that wiping out this shark species,

or any shark species, will have massively devastating impacts on the ocean, and

therefore on all of us.

As the ocean advocacy challenge

continues, it’s always bridging this relationship — between humans and the sea

— that eludes being truly embraced by the masses. Many people on the planet

will never see the ocean, let alone experience it, or better yet interact with

our counterparts.

Following these excursions, our

minds collectively reel for days, even weeks, about how to bridge that

connectivity gap for the masses.

Ten people aboard a small boat 30 miles off the Rhode Island coast very quickly become ambassadors to and for the sea, and there are billions of people needing to hear that voice.

Ten people aboard a small boat 30 miles off the Rhode Island coast very quickly become ambassadors to and for the sea, and there are billions of people needing to hear that voice.

Michael Lombardi is a Rhode Island

resident who has worked as a professional diver for more than 20 years. His

work focuses on advancing technology and techniques for improved human

intervention within challenging underwater environments. He’s also the founder

of Ocean Opportunity Inc.

Editor’s note: This year’s blue

shark journey was organized by Ocean Opportunity Inc., in cooperation with

Snappa Charters. Contributing participants include Karina Scavo, Katey

Lesneski, Nicola Kriefall, Adelaide Lindseth, Brooke Benson, Kate Platek, Adam

Piispanen, and Michael Lombardi who are responsible for the above photographs.