Looking for prevention for this intestinal scourge

Kate Schweitzer1, JAMA

Medical News

This past winter, cases of norovirus, a highly contagious stomach bug characterized by sudden vomiting and diarrhea, surged in the US. Nicknamed the “Ferrari of viruses” for how fast it spreads, it’s also known for racing through cruise ships, long-term care facilities, and school cafeterias. But, according to those who study it, the virus hasn’t gotten the attention it deserves.

The virus is a leading cause of

acute gastroenteritis worldwide. In the US, it causes more than 50% of

all foodborne illnesses. And each year it accounts for nearly half a million

emergency department visits, mostly for young children, and roughly 900 deaths,

predominantly in older adults, according to the US Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention.

In well-resourced regions, norovirus

symptoms commonly pass after a few extremely unpleasant days, but

“there are other places on the planet where diarrhea really does threaten the

health of populations, especially those already suffering from malnutrition,

chronic starvation, or dehydration,” said C. Buddy Creech, MD, MPH, director of

the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program at Vanderbilt University Medical

Center. “It’s a significant driver of mortality around the globe.”

Norovirus contributes

to nearly 1 in 5 episodes of diarrheal disease worldwide and causes

about 200 000 deaths

annually. The most vulnerable populations include children younger than 5

years, older adults, and people who are immunocompromised. In developing

countries, deaths from norovirus are common among children—who make up more than a third of the global death toll.

Preventive measures like improved water, sanitation, and hygiene have not proved effective enough to control the notably transmissible virus, which incurs a $60 billion cost to society—including $4.2 billion in health care costs—globally every year.

It’s for these reasons that the World Health Organization called developing a vaccine for it a priority in 2016. Since then, vaccine developers have struggled to create a safe and effective option. Currently, a handful of candidates are in various stages of clinical trials, including one that would be offered in the form of an oral tablet—a promising approach for a virus with such a devastating grip on resource-limited nations.

“No one is developing a norovirus vaccine in order to avoid

the occasional cruise ship outbreak,” said Creech, who is also the Edie Carell

Johnson chair and professor of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt.

“We’re doing it so we can protect the world’s most vulnerable from potentially

devastating illness.”

Why Norovirus Is So Tricky

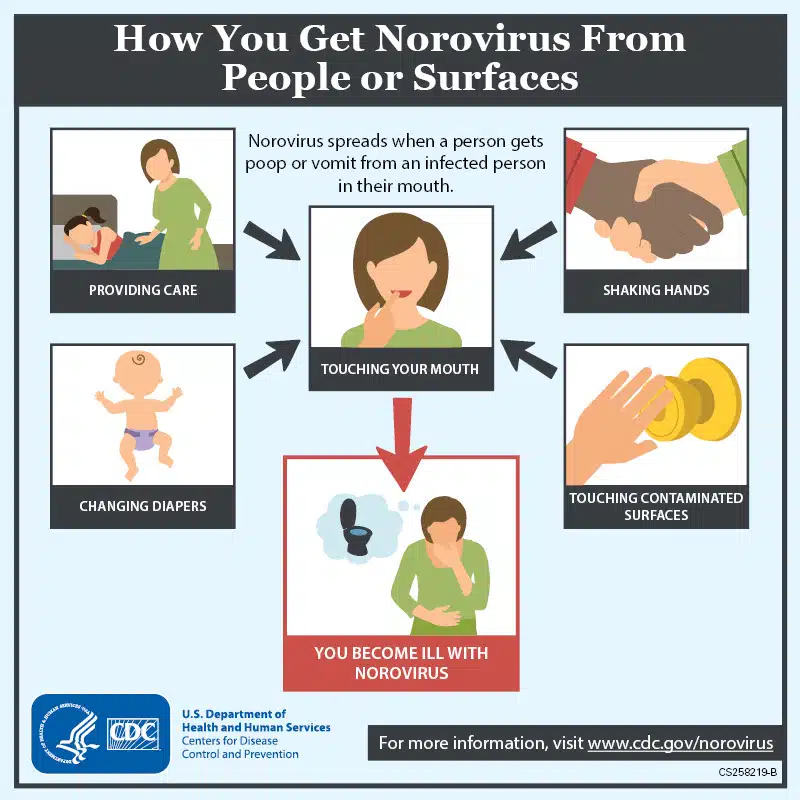

What makes the norovirus “incredibly tricky” to manage is,

in part, how it’s spread, said William Schaffner, MD, a professor of preventive

medicine and infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“It’s not just touching and then ingesting from contaminated

surfaces,” he said. “It can also spread through the air. You can actually

inhale the virus, and just a trace of it is enough.” Not only that, people who

have recovered from the infection can continue to shed the virus for weeks, and

it can live on surfaces for even longer.

In addition to its most noteworthy adverse effects,

norovirus infection can also cause fever and headaches, which is why Schaffner

said it’s often referred to as a stomach flu despite being unrelated to

influenza.

Variability in the severity of norovirus illness adds to the

complexity. As Creech noted, the “disease burden is a U-shaped curve” in terms

of demographic risk.

“Most people recover, but the very young and those older,

frail people are the ones who run into trouble and end up in the hospital to

get rehydrated,” Schaffner said.

These factors make norovirus a “perfect pathogen,” noted

Lisa Lindesmith, MS, a senior scientist who is studying the virus at the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It’s highly infectious, it’s very

environmentally stable, and there’s a tremendous amount of diversity within the

family.”

But a perfect pathogen makes for a challenging task, rife

with scientific barriers, for vaccine developers.

Based on genetic differences, researchers have divided

noroviruses into nearly 50 genotypes split into 10 groups. Five of these

groups are known to infect people, with genotype I (GI) and GII being most

common. Similar to influenza virus, dominant norovirus strains change and evade

immune systems. GII.17

caused most of the norovirus cases in the US this past winter, when

there were 2630 outbreaks—nearly double those of the previous year.

Meanwhile, GII.4, known as Sydney, has

been the most prevalent strain for more than a decade and the one associated

with the most severe illness.

“These GII.4 viruses are the ones that cause pandemic levels

of disease and cyclical patterns over time,” Lindesmith said. “They are

particularly good at changing themselves, which leads to evasion of the

immunity that you’ve already developed. When you think about young children who

have the most severe disease, it’s easy to see what a challenge this is. We’ve

got an immature immune system that’s going to need to build through repeat

exposure, yet we have a virus that’s continually changing.”

On top of that, researchers don’t know how long immunity

lasts after a norovirus infection—depending on the study, estimates range

from several months to up to 9 years. And human norovirus cultivation has not

been possible until

recently: “It’s rather difficult to grow it in laboratory conditions, so

that’s caused delays in development as well,” Schaffner said of vaccine

research.

The Challenges Facing Norovirus Vaccine Makers

Scientists have taken several different approaches toward a

norovirus vaccine, but all have progressed in fits and starts.

One of the most advanced vaccine candidates contains

viruslike particles (VLPs), empty structures that imitate the size and shape of

the pathogen but lack its genetic material. “It looks just like the virus to

your immune system, so, in theory, you can make the appropriate response

without being exposed to the replicating virus,” Lindesmith said of this

vaccine technology, which has so far been used to protect against human

papillomaviruses and hepatitis B and E. Developers have posted positive efficacy and immunogenicity data

for the investigational VLP norovirus vaccine in adults but the same candidate

failed to protect infants in a trial, manufacturer HilleVax announced in

July 2024.

Moderna, which has also been at the forefront of norovirus

vaccine development with its single-dose messenger RNA–based candidate,

mRNA-1403, had its own setback, the pharmaceutical company announced in

February. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put a temporary hold on a

phase 3 clinical trial of mRNA-1403 following a single reported case of

neurological disorder Guillain-Barré syndrome. The trial launched in September

2024 with a recruitment goal of 25 000

participants globally.

Moderna did not respond to a request by JAMA Medical News

for comment, but noted in its press release that an investigation was under way

and that it “does not expect an impact on the study’s efficacy readout

timeline.”

Another platform, live-attenuated vaccines, has been

successful for rotavirus and influenza, but Lindesmith said it’s not currently

possible to grow the norovirus at the scale necessary for this. Still, new

discoveries may make this possible in the future. Over almost a decade of work,

scientists have made significant advances in

norovirus cultivation, and in January, researchers from Baylor College of

Medicine in Houston showed that they were able to reliably grow the virus in a

“mini gut,” an

organoid culture system that mimics human intestines.

Another novel approach involves piggybacking on the highly

effective vaccines for rotavirus, an unrelated pathogen that also causes

diarrhea. Researchers engineered an

experimental combination vaccine by adding a key protein from

norovirus to a harmless strain of rotavirus, and it induced the production of

neutralizing antibodies against both. The results, while encouraging, were from

preclinical studies of mice—which are not representative of human norovirus

infection—and the researchers still need to demonstrate that the immunized

animals are less likely to get sick from norovirus before it can move forward

as a solution for broad-spectrum protection.

The Potential for a Norovirus Pill

Most recently, a biotech company has sought to bring a

norovirus vaccine to market with a pill. Administered orally in a coated tablet

form, Vaxart’s delivery platform is an adenovirus

vector vaccine designed to stimulate mucosal immunity, which could be

the key to preventing norovirus infections at their starting point, said Becca

Flitter, PhD, MPH, director of immunology at Vaxart, which also has an oral

influenza vaccine in development.

In May, researchers published

promising data on the pill from a trial during which participants were

intentionally exposed to the virus.

“Unlike a large trial with 30 000

people where we only see who gets disease and who doesn’t, a

challenge study like this one allows scientists to get blood samples and even

stool samples in the hours or days before symptoms occur, so they get to know a

lot more about the actual cadence and rhythm of the response to the vaccine,” Creech said.

Half of the nearly 150 participants, aged 18 to 49 years,

received the oral vaccine, and a month later, all participants ingested the

GI.1 strain of norovirus in a liquid dose “hard enough” to ensure people got

infected, Flitter noted.

By the following week, 82% of the placebo group was infected

compared with 57% of the vaccinated group, a 30% relative reduction.

Additionally, Flitter and her coauthors found that those who received the

vaccine shed less virus in their stool and vomit than those who got the

placebo, suggesting the vaccine could slow the spread of the virus.

The reduction in the severity of disease symptoms, however,

was not

statistically significant. Flitter said this may be due, in part, to the

fact that participants received higher amounts of virus than they’d encounter

in real-world settings.

This phase 2 proof-of-concept study, which appeared in Science

Translational Medicine, followed previous analyses that found the

tablet induced mucosal

immunity in older adults and broadly

neutralizing antibodies against norovirus. In a press

release, Vaxart also announced results of a trial focused on breastfeeding

mothers: it showed an increase in norovirus antibodies in their breastmilk,

which suggests the potential for passive transfer to infants.

Lindesmith, who coauthored two of the studies on the oral

pill with Flitter, acknowledged that the strain they tested, GI.1, isn’t

responsible for the bulk of global infections. “We really have the

epidemiological data to support this need for GII.4 to be the target as a

matter of public health,” she said.

In June, Vaxart reported in a press

release that a second-generation version of the vaccine protected

against both GI and GII viruses in a phase 1 trial and, according to Flitter,

the candidate has “greater potency and enhanced immunogenicity in humans.”

Flitter said she’s excited about the possibility of “forging

a new path” with the tablet format.

“With a pill, you don’t need the infrastructure you need

with a needle,” she said. “You don’t need trained professionals who know how to

inject. You can keep it at room temperature, so bags of pills could be shipped

to wherever there’s a need, with no medical waste.”

This will work well with the at-risk older adult population,

but not the other side of that U curve, Creech noted. “My anticipation is that

we start with an oral tablet and move into a liquid formulation, like we do

with oral rotavirus vaccine, that can be given to [infants and] younger

children,” he said, adding that this will take time. “Hopefully through

vaccinating adults first, we can start to reduce the likelihood of transmission

to those who are most vulnerable who cannot yet be vaccinated.”

Of course, without an approved vaccine, these considerations

are still a long way off. Vaxart has yet to begin a phase 3 trial of its oral

pill. Flitter is currently prepping phase 2b trials for the second-generation

version.

Lindesmith acknowledges the challenges that still lie ahead.

She said the field is “not just solving for the GII.4 of today but also the

GII.4 of tomorrow” and estimates the earliest possible approval for any

norovirus vaccine is still years away. Creech predicts that an application to

the FDA is 5 years out.

Even then, most experts predict that, due to norovirus’s

rapid evolution, a vaccine will function much like flu shots and require

regular boosters. But “something is better than nothing,” Schaffner said.

“If it’s not preventing the virus altogether, we want to see

the disease blunted at the very least,” said Creech, who suggested

administering it in anticipation

of an outbreak or in advance of travel. “Driving down the burden of

this illness has tremendous societal benefit.”

Article Information

Published Online: July 25, 2025.

doi:10.1001/jama.2025.10673

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Creech

reported receiving grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the US

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Moderna and serving as a

consultant for Sanofi, Merck, TDCowen, Guidepoint Global, Delbiopharm, and

Dianthus. He also reported serving on the data and safety monitoring board for

GSK and Bavarian Nordic. Ms Lindesmith reported holding patents on norovirus

vaccine and therapeutics designs, including coinventorship with Vaxart. She

also reported ongoing collaborations with HilleVax, GIVAX, Vaxart, Merck, and

Maine Biotech related to norovirus vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics and

that she has served as an external consultant for HilleVax and Merck. Dr

Flitter reported owning stock options in Vaxart and that funding for all

clinical trials she authored was from Vaxart except for the maternal breastmilk

study conducted in South Africa, which was partially funded by the Gates

Foundation. No other disclosures were reported.