A yes vote by CRMC would be essential to permitting the offshore wind project

By Mary Lhowe / ecoRI News

contributor

|

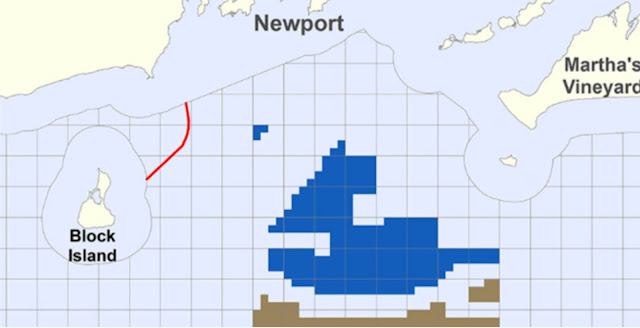

| The Revolution Wind facility is proposed for federal waters off the coast of Rhode Island and Massachusetts. (BOEM) |

Mindful of concessions and mitigation actions promised by the developers of the proposed Revolution Wind project, staff of the Coastal Resources Management Council have recommended the council vote yes on the project, thereby declaring that it conforms with the state’s coastal management plan.

But after hearing four hours of arguments from fishermen

and the public at its April 25 meeting and with several people still waiting to

comment at 10 p.m., the CRMC board took no vote, continuing the matter to its

May 9 meeting.

A yes vote, declaring that the project is consistent with

the state’s Ocean Special Area Management

Plan, would be essential to permitting the wind facility, which

still is awaiting final approval on the federal level from the Bureau of Ocean

Energy Management (BOEM).

“Mitigation and project modifications” to which developers Ørsted and Eversource have made commitments “will allow the project to meet our policies,” said Kevin Sloan, an analyst working for the council.

The Revolution Wind project, in the planning for years,

would position about 65 turbines across 84,000 acres of the Outer Continental

Shelf about 15 miles southwest of Point Judith. When completed, it is expected

to deliver 704 megawatts (MW) of power, of which 400 would be bought and used

in Rhode Island and 304 would go to Connecticut. The project would have two

offshore substations. Export cables on the seafloor would bring power to the

land-based grid at Quonset Point.

The final environmental impact statement for the project

is expected to be published in June. Construction work, if the project is

approved, would begin in 2024, starting with seabed preparation beginning in January,

foundation and turbine placement in May, cable installation in July, and

remediation, if needed, toward the end of that year.

Attorneys for the Fishermen’s Advisory Board (FAB), which

is extremely wary of the project, along with Ørsted and Eversource, the two

co-developers of Revolution Wind, presented statements to the council. Speakers

also included people arguing for the need for renewable energy and local

fishermen, who fear the impact of the 84,000-acre project on important fishing

grounds, including the revered Coxes Ledge, a

habitat for cod.

The plan has been under study by the council for a year

and half, a period that included a lot of negotiation with Ørsted and the

commercial and recreational fishing communities.

Ørsted has promised to create a fund of $12.9 million to

compensate fishermen for losses due to construction and operation of the

project over its lifetime of about 30 years. Rate of loss is estimated by

Ørsted and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute at 5% annually. Ørsted would

also put money into a fund to study the environmental impacts of the wind

facility over time.

In contrast, a FAB spokesperson said an appropriate amount

for the fund based on losses to the industry would be $21.6 million.

To ease concerns of fishermen and others worried about

the impact on the ocean, Ørsted reduced the number of planned wind turbines to

65 from 100. Ørsted representatives said turbine locations were eliminated to

entirely avoid areas of glacial moraine on the seabed, which is complex hard

surface where some important fish species live and feed.

The original grid layout of the turbines, spaced 1

nautical mile apart, would look more like a web, Ørsted representatives said,

because some turbines would be microsited, meaning their position would be

adjusted and fine-tuned to avoid sensitive areas of the seafloor.

Boulders on the seafloor are a sensitive topic because

they can snag, tear, and break fishing gear, and experienced fisherman already

know where they are and how to avoid them. Ørsted said it would make an effort

to move boulders, as needed, into piles, making them more concentrated and

predictably positioned. Ørsted said it would reposition some seafloor cables to

bypass complex and essential fish habitats.

Fishermen and other speakers who worry about the impact

of the project on the ocean spoke forcefully at the meeting, individually and

through FAB attorneys.

Marisa Desautel, a lawyer for the FAB, said the

developers’ “conditions do not go far enough to mitigate the impact of this

project.”

During public comment, fishermen spoke in far more

emotional terms. Chris Brown, a commercial fisherman and member of the FAB,

called offshore wind “tremendous ecosystem disruptors.”

Shifting gears, Brown said, “There is a religious

arrangement that fishermen have with their grounds. It is sacred. Mitigation

measures will help, but they are not a solution. We don’t think there is any

level of mitigation that could affect the deleterious effect [of wind farms] on

the Atlantic Ocean.”

Speaking of the value of renewable energy, Brown said,

“My kids and grandkids need green energy, but must we accept environmental

compromise?”

One speaker, a wind farm opponent but not a fisherman, was Elizabeth Knight, who raised objections about navigational safety within the wind farm.

She said the Coast Guard has declared that a symmetrical grid pattern for the turbines makes navigation safer, whereas a less-symmetrical grid caused by micrositing to avoid important habitats can contribute to “radar scattering” that make radar less effective and seamen less safe.

Knight said a

Congressional committee has expressed concern about a lack of attention by wind

farm planners to Coast Guard comments. Knight identified her presentation by

her name, but she also is a director and main spokesperson for the East Bay

anti-offshore wind group Green Oceans.

One speaker and wind farm supporter, Tom Clemow, urged

the council not to expect or require 100% certainty about offshore wind. “It is

not possible to know everything about how the project will affect fish or the

fishing community,” Clemow said. “Just because we don’t know everything about

everything is not a reason not to do this.”

Speaking later, J. Timmons Roberts, a professor of

environmental studies and sociology at Brown University with expertise in

climate science, addressed Brown’s question about tradeoffs between ocean

health and securing green energy. He reminded the council of the fundamental

rationale for developing renewable wind energy: the need to eliminate the

burning of fossil fuels, which are warming the Earth’s climate to a dangerous

degree.

“Temperatures are rising. Carbon dioxide is accumulating

in the atmosphere. This stuff stays up there for hundreds of years,” Roberts

said. Hitting the pocketbook issue, Roberts said Rhode Islanders spend $3

billion a year importing sources of fossil fuel energy from outside the state,

even as high winds above the Atlantic provide endless power. “We have to act,”

Roberts said. “We have an awesome resource right here.”

Roberts said many of the fears surrounding offshore wind

are “speculative and unsupported by research.” He noted that offshore wind is a

known and studied industry, with 5,400 turbines spinning as of 2021 in waters

off the coast of Europe.

“We are not going to fall off a cliff here,” he said.